Happy Birthday to OrioledHub

31 May, 2022

Overview of drug registration in Vietnam in the period 2009-2019

8 June, 2022The European system of approval of new medicines comprises an European Union (EU)-wide authorisation procedure (the so called centralised pro- cedure) alongside national procedures based on different EU Member States working together and recognizing each other’s evaluations (the so-called decentralised and mutual recognition procedures). It is a system that has evolved over the past half-century from one with wholly separate national systems to one where EU countries now harness their regulatory and scientific expertise to harmonise and improve the evaluation of medicines across Europe. Today, the purely national procedure is rarely used by applicants and only when they seek marketing authorisation in a single Member State. Although the different procedures may give an impression of complexity, they have simplified the authorisation process across Member States, reducing the times for new medicines to obtain marketing authorisation and improving patient access to new medicines.

The current European system of medicines approval consists of a centralised authorisation procedure as well as national authorisation procedures based on simultaneous authorisation in more than one European Union (EU) Member State and the mutual recognition of marketing authorisations. In addition, there are medicines authorised in single Member States under purely national procedures. The centralised procedure and the European Medicines Agency, which manages the procedure, have both been in operation since 1995. This paper describes the history of the approval system and the harmonisation that has occurred over the past half-century and gives an overview of the way medicines are approved in the EU today.

The history of the pharmaceutical regulation system in Europe

Although many European countries have long had laws regulating the use of various medicines, modern pharmaceutical regulation in Europe can be considered to have started in the 1960s and has not stood still since. In the aftermath of the thalidomide tragedy, there was increased legislative control of pharmaceuticals, with regulatory agencies being created all over Europe to approve medicines and Member States working on European harmonisation, leading to the first pharmaceutical Directive in 1965 (Council Directive 65/65/EEC). The Directive required all medicines to have a marketing authorisation and also aimed at harmonising standards for the approval of medicines within Europe. In addition, this law encouraged the cre- ation of a single market for pharmaceuticals in the EU at a time when every country had its own separate approval procedures which meant that companies had to submit separate applications for approval of a medicine in each country.

In 1975, two Council Directives were introduced, the first (Council Directive 75/318/EEC, 1975) relating to the testing of medicines required to be carried out by companies seeking a marketing authorisation, and the second (Council Directive 75/319/EEC, 1975) establishing a procedure for marketing authorisation with the aim of promoting the free movement of medicines. The procedure was based on the mutual recognition of national assessments whereby a company could seek marketing authorisation for a medicine in one Member State on the basis of an existing marketing authorisation in another. The Directive also established an advisory committee to the European Commission called the Committee on Proprietary Medicinal Products (CPMP) to help EU Member States to adopt a common position with regard to decisions on issuing a marketing authorisation. However, the opinions of the CPMP were not binding and the system had come under criticism for being slow, bureaucratic, and ineffective, with Member States failing to recognize each other’s assessments and seeking arbitration from the CPMP on nearly every occasion.4 The procedure was called the ‘CPMP procedure’ and was later simplified and became the ‘multi-state licensing procedure’. However, the procedure, though improved, was still considered by many to be ineffective and was little used by industry.5 In 1985, the single market project was launched, which included plans for the creation of the European Medicines Agency. In 1986, a new procedure for the authorisation of medicines called the ‘concertation procedure’ was introduced. This procedure was mandatory for biotechnology medicines, requiring a community-wide licensing opinion by the CPMP for these medicines before marketing authorisations could be granted in any Member State. However, this opinion was again not binding on Member States and Member States could still approve or reject applications without reference to the opinion.

A major step in harmonisation was taken in 1993 with the Council Regulation (EEC) 2309/93, which established the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, now known as the European Medicines Agency. In addition, the concentration procedure was modified and became the centralised procedure. The Regulation, which came into force in 1995, also re-established the CPMP as a ‘new’ CPMP to issue the Agency’s opinions on the granting of marketing authorisations in accordance with the centralised procedure, which now led to legally binding Commission decisions. The CPMP was later renamed the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP).

As the mandatory scope of the new centralised procedure was limited to biotechnology medicines, it replaced existing national procedures for these medicines. The concept of mutual recognition for other medicines remained and was introduced into European pharmaceutical law in 1993 (Council Directive 93/39/EEC, 1993).

By 1995, a harmonised European system of medicines approval had therefore emerged consisting of a procedure based on mutual recognition of marketing authorisations by Member States on the one hand and a procedure providing a community- wide licensing opinion on the other hand. The mutual recognition procedure had two precursors: first, the CPMP procedure which operated from 1976 to 1985; then the multi-state licensing procedure in operation from 1985 until 1995, which in 1995, became known as the mutual recognition pro- cedure. The procedure providing a community wide licensing opinion, the centralised procedure, developed from the concertation procedure which operated from 1986 until 1995. Whereas the early procedures were hampered by a lack of binding opinion by the CPMP, by 1995 this was no longer the case and pharmaceutical regulation in Europe had become better harmonised and more effective. After 1995, additional changes were made to this European approval system to further strengthen it. They included the introduction, in 2005, of a new procedure called the decentralised procedure which sought to avoid the potential for disputes which was identified over time as a problem with the mutual recognition procedure as Member States in which approval is sought were not involved early enough in the evaluation.

The current EU system

The centralised procedure

The advantage of the centralised procedure is that it requires a single application which, if successful, results in a single marketing authorisation with the same product information available in all EU languages and valid in all EU countries, as well as Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway. The scientific assessment of the marketing authorisation application is carried out by the CHMP. The scientific review process consists of alternating periods of active evaluation and periods during which the clock is stopped in order to give the applicant time to resolve any issues identified during the evaluation. In total, the duration of the process is up to 210 ‘active’ days before an opinion is issued by the CHMP.

Once an opinion has been given, it is forwarded to the European Commission which then has 67 days to issue a legally binding decision on the marketing authorisation. The mean approval time for medicines in 2012 approved by the EMA was 14.8 months. Once a marketing authorisation has been granted, the applicant can start to market the medicine in any EU Member State of its choice. However, in practice before a medicine is marketed, it will be subject to pricing negotiations and a review of its cost-effectiveness. This is carried out at national level by Member States to determine reimbursement criteria.

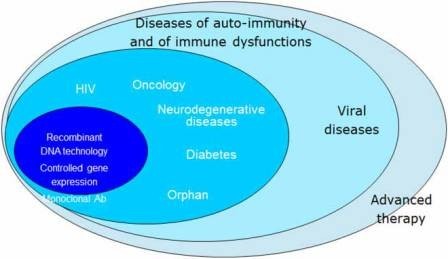

Initially, the centralised procedure was mandatory only for biotechnology medicines, as was the case with the previous concertation procedure. Over time, however, the mandatory scope of the centralised procedure has been gradually expanded and by 2005, it included orphan medicines (medicines for rare diseases) as well as human medicines that contain a new active substance (not previously authorised in the Union before 20 November 2005) and that are intended for the treatment of AIDS, cancer, neurode generative disorders, diabetes, auto-immune and other immune dysfunctions, and viral diseases. In 2009, the centralised procedure also became mandatory for advanced therapy medicines. The centralised procedure is also optional for other medicines that contain a new active substance not authorised in the Union before 20 November 2005, and for products which are considered to be a significant therapeutic, scientific, or technical innovation, or for which an EU-wide authorisation is considered to be in the interests of public health (Figure 1).

The first medicine authorised under the centralised procedure was the fertility treatment Gonal-F in October 1995. The EMA now receives around

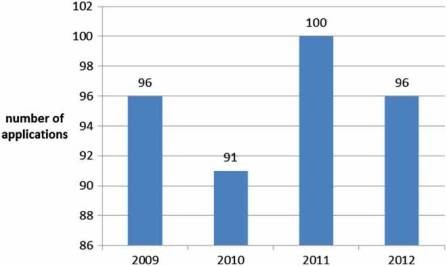

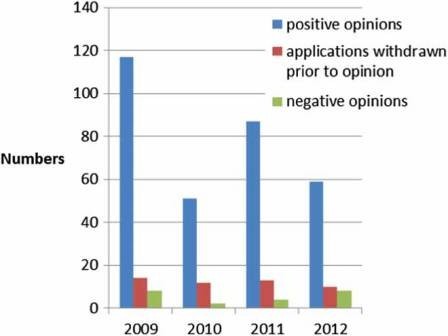

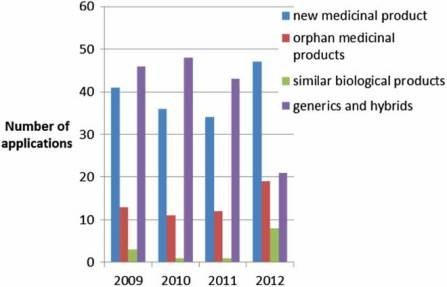

100 applications per year (Figure 2) of which, around 10% do not result in an opinion but are withdrawn, and around 5% result in a negative opinion (Figure 3). Since the establishment of the agency in 1995, over 700 human medicines have been approved using the centralised procedure. In the early years, only innovative products were approved via the centralised procedure but as data exclusivity for the first products approved began to expire, generics were also approved centrally. The number of applications for generics using the centralised procedure has increased over the years, peaking in 2010 with around 50% of all applications being generics (Figure 4). Today, most medicines containing a new active substance are approved using the centralised procedure.

Figure 1: Mandatory scope of the centralised procedure.

Figure 2: Number of applications received yearly by the EMA (2009–2012).

Figure 3: Outcome of evaluation (2009–2012).

Figure 4: Type of application received by the EMA (2010–2012).

The mutual recognition procedure

The mutual recognition procedure has been in place since 1995 and evolved from the multistate licensing procedure. The applicant must initially receive national approval in one EU Member State, referred to as the ‘reference Member State’ and then seek approval for the medicine in other, so-called ‘concerned Member States’ in a second step based on the assessment done in the reference Member State. This process has significant differences from the former multi-state licensing procedure, notably the requirement that disagreements between Member States must now be resolved at EU level. Disagreements are handled by the Co-ordination Group for Mutual Recognition and Decentralised Procedures – Human (CMDh), a body representing Member States, which is responsible for any questions in two or more Member States relating to the marketing authorisation of a medicinal product approved through the mutual recognition or the decentralised procedure.

If there is a disagreement between Member States on grounds of a potential serious risk to public health, the CMDh considers the matter in order to reach an agreement within 60 days. If this is not possible, the procedure is referred to the CHMP in a procedure called a referral. The CHMP will then carry out a scientific assessment of the relevant medicine on behalf of the EU.

In contrast to the previous procedure, the outcome of the CHMP is binding on the Member States involved once it has been adopted by the European Commission. The timelines for assessment by CHMP is 60 days.

Since the introduction of the decentralised procedure, the mutual recognition procedure is used for extending existing marketing authorisations to other countries.

The decentralised procedure

In the decentralised procedure, the applicant chooses one country as the reference Member State when making its application for marketing authorisation. The chosen reference Member State then pre- pares a draft assessment report that is submitted to the other Member States where approval is sought for their simultaneous consideration and approval. In allowing the other Member States access to this assessment at an early stage, any issues and concerns can be dealt with quickly without delay, which sometimes is known to occur with the mutual recognition procedure. Compared with the mutual recognition procedure, the decentralised procedure has the advantage that the marketing authorisation in all chosen Member States is received simultaneously, enabling simultaneous marketing of the medicine and reducing the administrative and regulatory burden. Today, the decentralised procedure is mainly used for applications for generic medicines.

As for the mutual recognition procedure, disagreements are handled by CMDh or the CHMP in case no agreement can be reached at CMDh level. In summary, the current procedures for approving medicines in Europe have resulted from a drive to harmonise and improve medicines regulation and have, for most medicines, replaced approvals based on purely national authorisations. Over the years, the scope of the centralised procedure has been widened and today most medicines containing new active substances are approved using the cen- tralised procedure. The mutual recognition and decentralised procedure are mainly used to extend existing marketing authorisations or for generic medicines. Half a century of harmonisations has led to a system that is simplified, improving access to medicines by reducing the times for new medicines to obtain a marketing authorisation.

Cre: Inga Abed/European Medicines Agency London, UK

Info: Inga.abed@ema.europa.eu